Since her arrival in Saigon as a seven-year-old in 1996, Mara Hurst has had a front-row seat to the country’s transformation from a “sea of two wheels” to the high-tech hub of 2026. After a tenure at the Canadian Chamber of Commerce, the marketing veteran sits down with The Saigon Times to reflect on 30 years of “quiet kindness,” the evolution of Vietnamese coffee culture, and her new mission to bridge generational gaps through a creative collective built on heart and soul.

The Saigon Times: Could you please introduce yourself and share your history with Vietnam?

Mara Hurst: My name is Mara Hurst. I am 36 years old and moved to Vietnam in 1996 when I was just seven. We moved here because of my father’s work. After high school, I briefly moved back to the Philippines for university, but I missed Vietnam—my parents and my life were still here. I returned and completed my degree in Professional Communications in Vietnam. Since then, I’ve spent over a decade in marketing and communications, starting as a copywriter for an advertising agency. I’ve lived here for almost 30 years now, met my husband here, and we are now raising our two children in the city I grew up in. I’ve left Vietnam more than once, but it has a way of calling me home every time.

How would you compare Vietnam in 1996 with the country we see today in 2026?

I will never forget leaving Tan Son Nhat airport in 1996. There were only motorbikes—maybe a few taxi cars—but otherwise, it was a sea of two wheels. Coming from Manila, which was more Westernized at the time, Vietnam felt very humble and relaxed.

Today, the change is drastic. I remember my first days seeing four or five people on a single motorbike; it was “organized chaos,” but beautiful because everyone, regardless of status, was on two wheels. Now, seeing people in cars, on the new metro (line), or using the new bridges and airports represents the immense opportunity and development the country has supported. HCMC has grown up with me.

As the city modernizes, is there anything you feel nostalgic about losing?

While the new infrastructure—the bridges and the metro—is shocking and beautiful to look at now, I do miss the simplicity of the past. I feel nostalgic for the xe ôm drivers who used to sit on every street corner. I remember one specific driver on Dong Khoi who would always greet me and take me home to Thao Dien. Those drivers represented the “quiet kindness” of Vietnam. Though that kindness still exists, it has taken on different shapes as the city has evolved.

What aspects of the Vietnamese lifestyle do you find most interesting?

I am deeply inspired by the “coffee culture” here. In many countries, coffee is a commercial chore or a quick morning necessity. In Vietnam, it is about embracing life. Whether you are a student, a busy worker, or a driver, the cafe is a place to escape the chaos and connect. Growing up, I met classmates at cafes; later, I used them for brainstorming with colleagues.

Success here seems tied to having time for yourself and the people around you, without discrimination. It’s why I love living here. In fact, my ultimate dream is to one day open a cafe in the Philippines that offers this specific Vietnamese coffee culture.

You mentioned “quiet kindness.” How do you define the character of the Vietnamese people?

It’s about attentive, quiet gestures. If you are moving house and have a million things in a taxi, the driver will help you carry them without being asked. If you have a motorbike accident, people stop to make sure you are safe. In Western cultures, kindness is often displayed through big smiles and formal manners. In Vietnam, it’s deeper. People help because they want to, often expecting nothing in return. There is a profound emotional resonance in that.

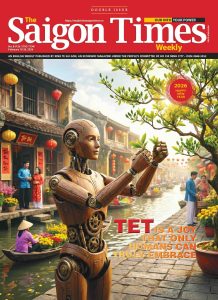

How do you typically celebrate the Lunar New Year (Tet) in Vietnam?

My best friends are from the former Vung Tau, so my husband and I often go there to celebrate with their family. We make banh chung together, decorate the home, visit temples, and play cards. It reminds me very much of Christmas in the Philippines—visiting relatives, offering food, and giving lucky money to children. It’s a time to return home to the people who love you. My advice to foreigners during Tet in HCMC is to stay in the city for a few days to enjoy the rare quietness, but then find a local friend who will invite you into their home. That is the only way to truly learn the culture.

You recently transitioned from your role as Executive Director at the Canadian Chamber of Commerce (CanCham). Why was now the right time for a change?

At CanCham, I helped Canadian companies enter Vietnam and build networks. That experience actually inspired me to pursue my own vision. After three decades here, I’ve seen a shift in how people connect. In the past, communities were built through word-of-mouth; today, they are digital ecosystems.

I am now building a collective—not just a company—that brings together creative, event, and communication professionals. My goal is to create events that aren’t just “one-offs” but are living relationships. I want to bring a decade of local understanding and advertising experience to create “experiences” that bridge the gap between Gen Z, millennials and older generations.

What makes a communication campaign truly resonate with a Vietnamese audience?

You cannot force a message. Authenticity is key. The Vietnamese audience is diverse, and you must create spaces where they feel welcome to be themselves, collectively. For example, in digital marketing, brands often try to force “user-generated content” campaigns that don’t always work because of the cultural value placed on “saving face.”

Vietnamese people generally don’t want to stand out individually in a loud way; they prefer to celebrate together. A successful campaign balances global experience with a local heart—understanding the “native tone” of how conversations actually happen here.

Can you share a project that you felt successfully captured this spirit?

In 2015, I created a festival called Southside Connection. It drew about 3,000 people. At the time, the music industry was different, and major brands were hesitant to sponsor music and the arts. We headlined with the rapper Suboi. The goal wasn’t about celebrities; it was about giving aspiring and ambitious young artists, musicians, designers and creators—a platform to celebrate their self-expressions. Seeing how popular those artists and the hip-hop scene have become now, in 2026, makes me proud. It showed that the culture was building toward something big.

What is your ultimate mission for the future?

I want to create a circularity within creativity and engagement. I want to use events and creative communications to raise money for communities in need, particularly for children who are less fortunate. I want to show them that success isn’t just about money; it’s about being “rich” in your lifestyle and community. Vietnam has given me so much, and I want to use my passion to support the next generation while helping professionals and creatives I collaborate with to find “heart and soul” in their work again.

Reported by The Ky