Present-day Asian cities are formed in a way similar to that of European urban centers during the Industrial Revolution. In the context of pandemics and globalization, industrial cities have exposed many shortcomings that need to be addressed.

In 2009, the population of Binh Duong Province was 1.06 million, 70% of whom were in rural areas. Ten years later, Binh Duong, a land-locked province with neither seaports nor river ports, whose only advantage was its proximity to HCMC, had made a spectacular change as 80% of its population were urban, which was the highest rate in Vietnam, even higher than in Hanoi and equal to that of HCMC.

This is the peak time of Vietnam’s foreign direct investment (FDI) attraction after she joined the World Trade Organization in 2007. For many years, Binh Duong remained the second-most attractive locality in Vietnam. Factories and industrial parks (IPs) have mushroomed in the province as a result of strong inflows of FDI into the manufacturing sector. Twenty-six years ago, in 1995, Binh Duong had its first industrial park, Song Than IP. Now the province hosts 30 IPs accommodating nearly 1,500 operational enterprises. By the end of 2019, effective FDI projects in Binh Duong had grossed total investment worth US$35 billion, second only to that of HCMC.

Binh Duong has undergone a major facelift. Surrounding the IPs are now estate systems and apartment buildings built to serve the growing population. More than half of Binh Duong’s current population are migrants from other localities who work in factories and enterprises. Some 24,000 apartments have been built there to be used by this work force, equal to one-sixth of the number in HCMC that has a population five times as large. The total retail space in Binh Duong amounts to 166,300 square meters.

In other words, a whole urban ecosystem has been formed to serve the livelihoods of the expanding urban population. This has been how industrialization is shaping Asian cities in the end of the 20th century and in the beginning of the 21st century.

Binh Duong’s story paints the picture of the changes in the formation of modern cities. During the time from the 15th century to the 20th century, Vietnam’s urban centers were built alongside river ports and seaports. It is not necessarily the case now because modern cities no longer totally rely on the favourable conditions created by rapid circulation and profitable commerce. Vietnam’s new cities now mirror the European samples during the Industrial Revolution, and resemble the way Asia is working now. This has been particularly true over the past three decades when Vietnam attracted a huge volume of FDI.

Vietnam’s cities will continue to develop in a way similar to how China’s cities have transformed themselves during the past 20 years. FDI continues to be channelled into the manufacturing industry. In 2019, FDI pooled into Vietnam’s manufacturing-processing sector reached a new record high of US$17.5 billion, or some 77.5% of the total registered FDI capital. In the preceding years, the capital inflow in this sector amounted to more or less US$15 billion.

During 2020 and 2021, in defiance of turbulences caused by the Covid-19 pandemic, foreign investment channelled into the manufacturing industry has remained high in accordance with the rule. For the entire 2020, the total FDI in this sector was US$13.6 billion, and during the first nine months of this year, the capital poured into the manufacturing industry reached US$12.7 billion, a rise of almost 19% year-on-year.

When production expands, industrial cities are formed by attracting migrant workers to address the problem of labor shortage. New urban dwellers are mostly migrants. The influx of workers moving toward or away from cities, however, are fertile ground for epidemic transmissions.

The fourth wave of Covid-19 in Vietnam soon swept through Binh Duong and turned the province into the second-largest locality in Vietnam when it comes to coronavirus infections, being behind only HCMC. By November 1, Binh Duong had had 233,740 infections, which mostly emerged over the previous four months, accounting for a quarter of the country’s total.

The number of infections is almost in tandem with how fast activities in a city are, in particular in newly emerging cities where the labor market remains loose. The complex structure in this case and the diversity of mobility provide a hospitable environment for the transmission of the coronavirus.

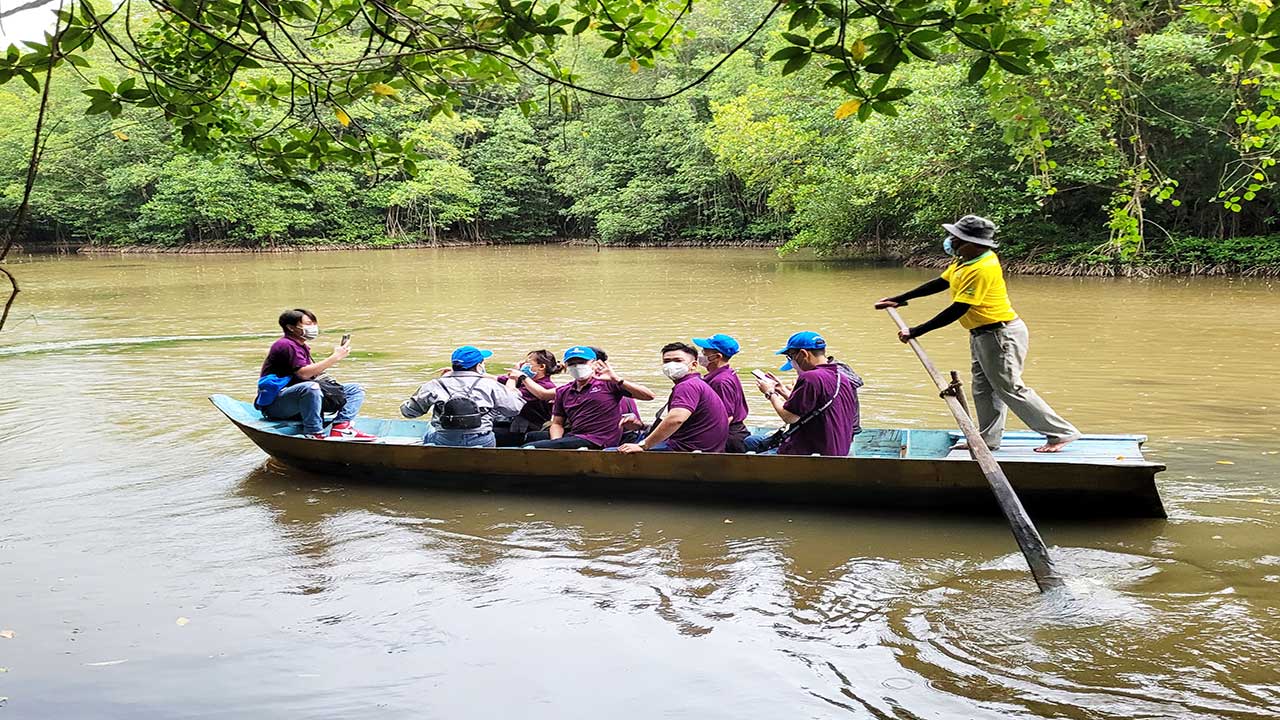

In relatively old cities, such as HCMC, infected cases were mostly found in inner districts whose population density and building density are high and where safety measures were disregarded. During the peak of the latest attack of the coronavirus, outlying districts, such as Can Gio or Cu Chi, were less vulnerable to the pandemic.

New revolutions, such as housing and living environment, are essential to cope with the dangers caused by the pandemic although they cannot be carried out overnight and it has to take into account the multitude of socioeconomic effects.

Gentrification, both urban structure and quality, is vital as economic damages inflicted by the pandemic are indisputable, especially human losses. Labor supplies were adversely affected because infected workers had to stop working. Worse, industrial parks had to be closed to suppress infection clusters. This is particularly true with cities which originate from industrialization. The risks of supply chain disruption have grave repercussions on the economy, not only in affected regions but also possibly on a global scale.

If a virus wreaking devastation equivalent to that of the virus causing the Great Influenza epidemic, or Spanish flu, in 1918 had returned in the current context of globalization and urbanization, it could have killed more than 100 million lives, even when vaccines and modern anti-viral drugs are available, according to a 2006 study conducted by Taubenberger and Morens. When Spanish flu broke out in 1918, it killed 50 million people and contaminated one-third of the world’s population. So far, Covid-19 has killed five million people worldwide.

According to estimation by the World Bank, in 2020, the global economy declined 4.3% because of the Covid-19 pandemic, a sag seen only in the Great Depression and the two World Wars.

It costs the whole world some US$570 billion to fight pandemics, from medium to grave, or 0.7% of global income. A pandemic of the caliber of Spanish flu, the cost may be as high as 5% of global GDP.